| ||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

No Homes for Tawny Owls Part 2: Why Tawny Owl chicks fall from open nests (Revised December 2007) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

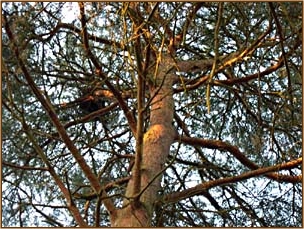

IF THEY CAN'T FIND A NICE HOLE to rear young in, Tawny Owls do the obvious thing. They use somebody else's old nest. This will often be an abandoned crow's nest, and in our area these tend to be near the tops of Scots Pines, as in the photo. Unlike a hole in a tree, or a nestbox, open nests are not a safe place for young tawnies. Crows' nests, for example, are not particularly large and have a shallow bowl, if any. Over the years they deteriorate, with the rain, wind, squirrels and birds gradually pulling them apart. Our mother owl used a crow's nest in 2003 that was already somewhat reduced. When she used it again two years later it was even more minimalist, and two more chicks were lost. In three successive breeding seasons she lost all her six chicks from two such nests when they fell to the ground at ages ranging from about 12 to 20 days. By 2006 the nest she used in 2003 and 2005 had completely disappeared. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Why are twig or stick nests unsafe for young owls? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

The reason is simple. They walk off backwards ... by mistake. The young of cavity- nesting owls appear to be programmed to behave hygienically in the confined space of a hole. Some species have ways of dealing with the nest hygiene problem. Parent House Sparrows, for example, remove droppings in their beak and dump them elsewhere. Others, like pigeons, don't bother. With Tawny Owls, from about 10 days old, when a chick wants to relieve itself it walks backwards until it bumps against the side of the nest hole and does its business there. This helps to keep the central area clean. This behaviour is readily seen with rescued nestlings. Placed on a table, when it feels the call of nature a chick walks backwards until it falls off. It will do this time and again, only learning to take more care when it's older. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Above right: A still from the OwlCam film The Hidden World provides a nice illustration of what happens when a Barred Owl chick needs to relieve itself. Here chick no. 3 has backed a short way to the wall. When its scut feathers touch the wall it stops and does its business (arrowed). If there is no barrier like the wall of this nestbox it will continue to walk backwards. On an open nest this can lead to a fall. These chicks are aged from 10 to 15 days, though as the identity of chick 3 isn't known its age is uncertain. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Another reason that's been advanced for why the chicks of some species fall off nests is jostling by siblings when a parent arrives with food. This may well be an additional cause of accidents with tawny owlets, but once you have seen their backwards-walk-to-poo behaviour it is difficult to doubt that it's the main reason they fall from the nest. This instinctively programmed behaviour, designed to promote hygiene in a cavity nest, places chicks at great risk if their parents have had to use an open nest. From about 10 days old, when they become capable of sitting up and preening themselves and are generally more active, they are at risk whenever they want to do a poo. The real danger period seems to be from 15 to 20 days, well before they are capable of flight. The youngest chick we had fall was about 12 days old, before she had opened her eyes permanently. The oldest was Sophie, who fell at about 20 days. In her case it may have been her somewhat casual attitude to hygiene that kept her a little longer on the nest! The other two chicks we know of fell at 15-18 days, when their eyes were just opening permanently. Two more were never found, and were probably eaten by foxes. Nestling vs fledgling behaviour It is difficult to believe that any of these flightless nestlings was meant to be off the nest. Nestling birds tend not to be adventurous or place themselves at risk. They may bounce and frolic in the nest, but there is no inclination to move beyond it. Curiosity and adventurousness start when they begin to exercise their wings and feel lift. Before this their instinct is to stay put. This self-preserving behaviour, followed by curiosity and exploration in the days before fledging (gaining the ability to fly at about 30 days), has been evident in the two tawny chicks I have reared. Two others, reared by a wild tawny mother in our nestbox (below right), showed no inclination to leave the nestbox before fledging. As is clear from the photo, they could have made their way out on to the ledge or the branch in front with ease. Others do leave the confines of the nest in the last week before fledging (i.e. at 27-32 days) but tend to stay nearby, with frequent returns to the nest, until they can fly. This is the behaviour known as "branching". Branching has been nicely filmed for another, closely related owl, the Barred Owl, where it's also characteristic of the week before fledging (see the link to the OwlCam DVD review near the bottom of this page). Studies by researchers tend to confirm this "play safe" behaviour by nestlings: the majority of tawny owlets in safe sites like nestboxes or tree cavities stay put until they fledge or shortly before (Coles and Petty, 1997; Overskaug et al, 1999; listed on my Tawny Owl references pages). In the Coles and Petty study 22 owl chicks left their nestboxes at between 29 and 36 days, with a mean of 32 days. Whether branching occurred prior to fledging is not reported. With the Cambridgeshire owls (reported on this website) the first owlet made it to the door at 26 days but none of the chicks left the box until their 29th or 30th day. Likewise, the three chicks from Hrsovo in northern Croatia pictured in the first part of this article left the apple tree hole on fledging, not before. So from the evidence I'm inclined to believe that the often reported behaviour of branching, referring to young owlets moving around on branches close to the nest, is based either on observations of chicks that have recently fledged or of late pre-fledged chicks, and that it does not apply to chicks younger than, say, 25 days. Climbing abilities A frequently made claim about tawny chicks is that if they fall from the nest they can climb back up. This is a statement that needs clarification as it almost certainly applies only to chicks older than 25 days, when they start to get lift from their wings. But the claim is usually made as though it applied to owlets of any age, including nestlings. I find it impossible to believe that the 12-20 day old chicks we have found on the ground have any ability to climb trees. For a start they may be injured and in pain. Second, they appear to have no idea which tree to climb if they could. The eyes of some haven't even opened fully. If they do move, they tend to walk until they find cover or the base of a nearby tree, where they sit helplessly. Third, as shown in the OwlCam DVD mentioned above, chicks need some flying capability to climb as climbing a trunk is done with a combination of beak, claws and lift from the wings. A flightless chick can't do this walk-flying. Fourth, I've seen no evidence of an instinct or ability to climb in pre-25 day chicks. They just sit tight, as nestlings should. Finally, in the few cases we have known, the mother appears to abandon flightless nestlings that fall to the ground. This may be because she judges that they are too vulnerable to predation. In the case of our first orphan owlet a rat was brought and left on the ground nearby, but it seems that when the mother found him unresponsive -- unable to eat the meal because of his injuries -- she abandoned him. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

The crow's nest in which our two orphaned owls began their lives. It has now completely disintegrated. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

A common sight: two tawny chicks rescued after a fall. One had made its way across a lawn and was found far from the nest. The other was in a wood. The Bengal Eagle Owl behind was born in captivity. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

A safe alternative . . These two tawny chicks peering from our nestbox did not leave before fledging at about 32 days despite an easy route out. All that was needed to keep them from harm was a low rise under the door to stop them backing out when pooing. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Another chick that fell. Sophie survived her fall because I'd removed branches below the nest days before. The shaved trunk can be seen in the second pic from top. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Related material on this site: Looking after an orphaned tawny chick The fate of two little owls who fell from the nest in 2004 (Very Young Owls) Intervention: we put up a nestbox (Nesting Diary 2006) Tawny Owl Nesting Diary 2008 (currently active nestbox log) Nestboxes for Tawny Owls -- A thorough look at nestboxes: planning for one, the different types, how to make your own and how to put one up. And more. OwlCam DVD. The nestbox illustration near the top of the page is used by kind permission of the author of this video. For a review of the film and more stills see the Owl Gallery page 9. In the scene pictured above the chick doesn't back far and contact with the nestbox wall is very gentle, but a week later (in footage not used in the DVD) the chicks were backing until they made solid contact with the wall before relieving themselves. Interestingly, too, these Barred Owl chicks appear to release waste in fecal sacs, which the mother clears up by eating them. So far I've seen no evidence of fecal sacs or waste removal by mother tawnies, whose chicks appear simply to eject large quantities of semi-liquid waste.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

powered by owls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

A crow's nest used by the two "Pine Nest" owls featured in the Nesting Diary 2006 (not clickable)